IN CONVERSATION: SOPHIE MAGEE

Fashion

IN CONVERSATION: SOPHIE MAGEE

Sophie Magee breaks down her deeply personal and political graduate collection in our latest post. She discusses the main influences on her identity, and how as a designer she channels her Northern Irish heritage into her work.

Words:

Emily Pearman

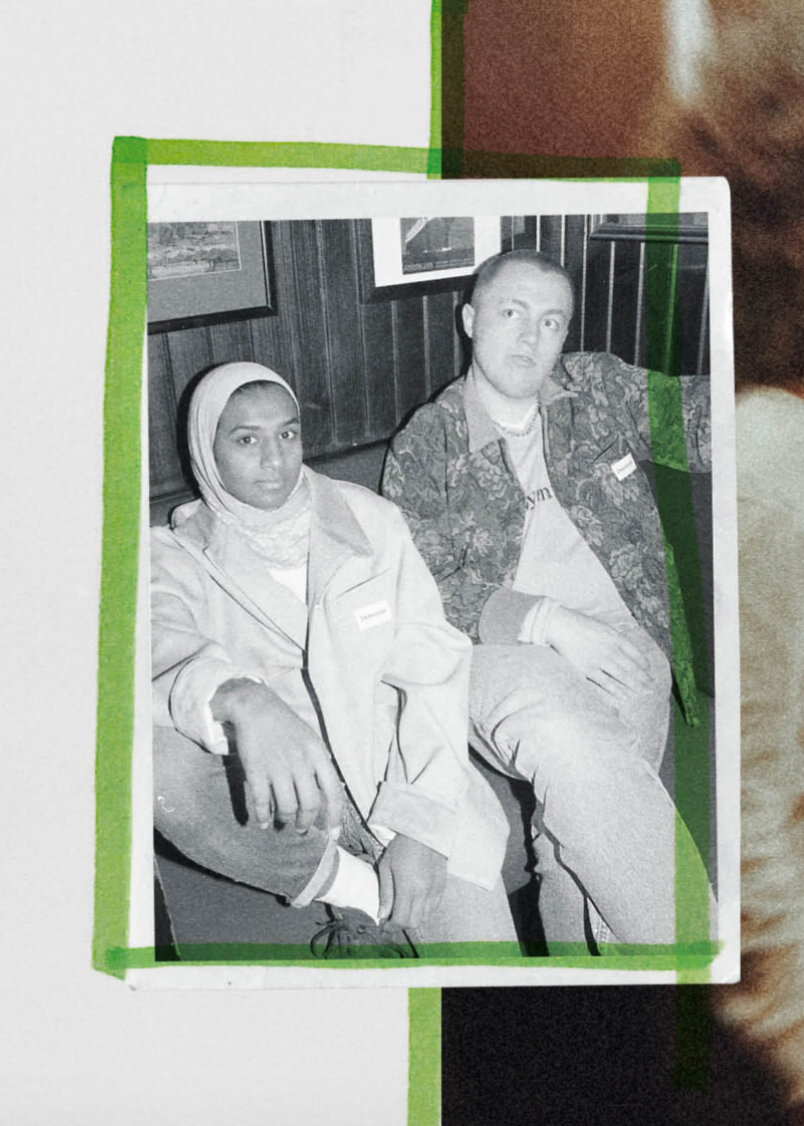

Imagery:

Archi Shah & Perry Gibson

BB: Sophie, you’ve had a busy few months of late, give us a rundown of life in the run-up to your show?

SM: Third-year, for any student, is the accumulation of years of work into an impactful graduate collection. For fashion students, this is how we present ourselves to the industry as designers. I had the best learning experience in my year out living and working in Amsterdam. To have the opportunity to work alongside the Runway Design Teams at Tommy Hilfiger, and closely help develop collections, working backstage at the shows and celebrity dressing. It gave me the grounding needed to build my collection this year. However, designing for an established brand, and designing for yourself are two very different entities.

It leads you to question who you are fundamentally and what your voice is within this industry. Minus a global brand and backing, to come back to the real world doing a graduate collection is an incredibly challenging experience. You are required to be the creative director of your brand, as well as, tailor, pattern cutter graphic designer, casting director, stylist and accountant. Endless hours of work, sleepless nights and tears. The lead up to the show was no easy ride.

BB: How important a role does your identity play in your design aesthetic?

SM: My graduate collection was an explorative process into my own identity. I found that now having distance and space from Belfast and Northern Ireland, I could question a lot more of who I was and where I come from. This collection was deeply personal looking specifically at my heritage and how I as a designer can channel that into my work.

The two main sources of inspiration where Frankie Quinn’s photography of boys rioting during the 70s and the Orange Order marching. My identity being of Irish descent became the fundamental reference point. How were The Troubles of the past reflecting the current political climate for the youth of today? I wanted to make a clear political statement with my collection to reflect the present with the past.

BB: What would you describe as the biggest contributing factor to your identity?

SM: Where I come from for sure, growing up in Belfast identity is imperative. Identity is drilled into you from flags to religion, to the walls you live beside and the school you go to. Green, white and orange, red white and blue, Catholic or Protestant? Communities are still segregated by walls put up during the troubles to keep the peace.

My parents brought me up in a mixed area of Belfast where I grew up less aware of sectarianism. This I believe is the biggest contributing factor to my identity allowing me to have a more objective viewpoint on these restraints and restrictions posed more forcefully in other areas of the city. To have the opportunity to attend art school in London and shaped my identity further. To find friends from all over the world with so many viewpoints has challenged my own identity and all me to grow more fully as a designer.

“

WHEN I DESIGN IT HAS TO HAVE MEANING, AS DESIGNERS WE ARE REQUIRED TO REACT WITH THE WORLD AROUND US AND QUESTION IT.

CAPTION GOES HERE: LORUM IPSUM

“

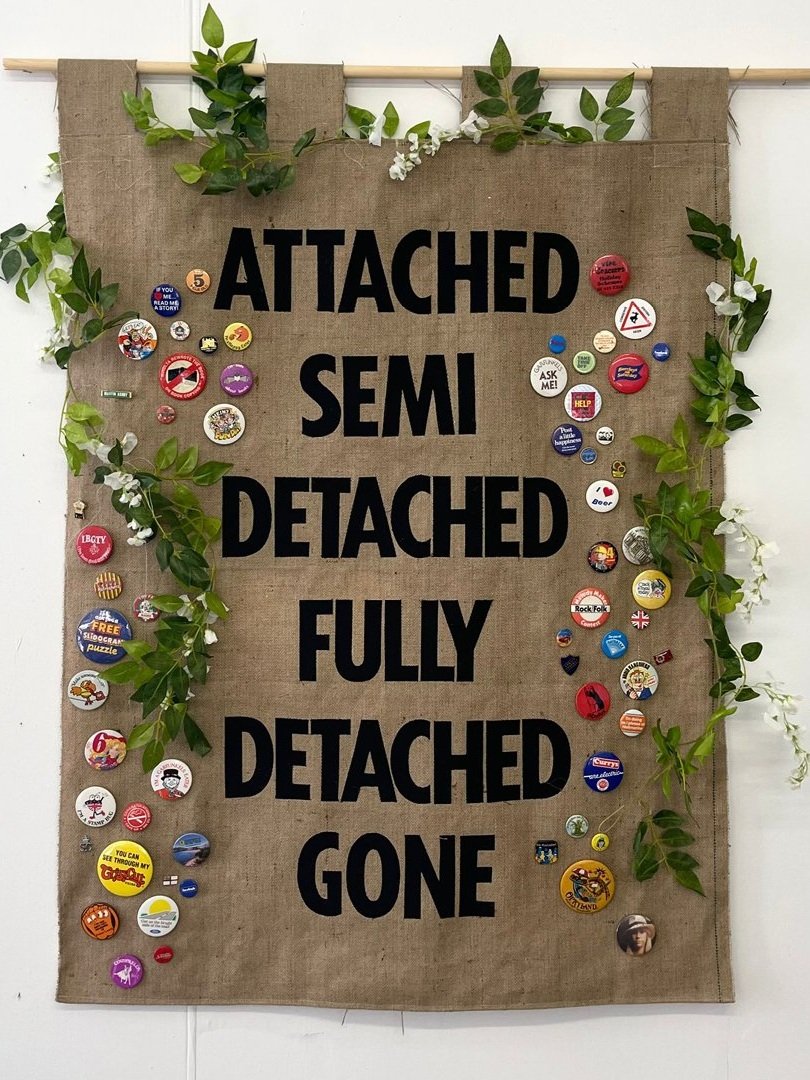

THE FOCUS OF MY PRACTICE IS TO SUBVERT THE USE OF TRADITIONAL EMBROIDERY BADGES AND DRESS WORN BY THE ORANGE ORDER TO MAKE A POLITICAL STATEMENT, MAKING PEOPLE QUESTION THE ACTIONS OF THE DUP, BY USING THEIR ICONOGRAPHY AGAINST THEM.

CAPTION GOES HERE: LORUM IPSUM

BB: What message are you trying to portray through your designs, and how do you hope to achieve this?

SM: This collection is deeply political. The focus of my practice is to subvert the use of traditional embroidery badges and dress worn by the Orange Order to make a political statement, making people question the actions of the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), by using their iconography against them. The leader of the DUP Arlene Foster is, in fact, a member of the Orange Order, I’ve taken a satirical standpoint and utilised this to compare the tensions of the past with the focus of Brexit today on Youth. The ‘European Youth District’ is reclaiming what the youth of Northern Ireland believe rather than what the DUP and Arlene Foster are bringing to the table with Brexit.

BB: Your show, with its location sitting in the bowels of parliament, instantly provokes a deep reaction. How important are the physical place and broader societal space in which you present your clothes?

SM: I couldn’t have asked for a better setting really, well maybe Downing Street with the leaders of both parties. For me, this grounded the collection precisely where it needed to be. A pro EU message coming from the youth of today within a political stronghold. Northern Ireland is going to be hit the hardest coming out of the E.U. and it just isn’t being picked up all that much in the House of Commons. If we look at the current economic climate, job losses and increased tensions in previous areas of conflict including riots in Derry, North Belfast, and bombs in Fermanagh, the collection gives a visual representation of History for a modern viewer.

By subverting the iconography of the Orange Order, it discusses directly the implications of Brexit on Northern Ireland and its current youth. The collection plays on this standpoint on politics and being shown in the House of Lords takes center stage where it is needed the most. It also just goes to show how little people understand or care when a collection that is emblazoned with this kind of iconography can get past security and it wasn’t picked up on. I loved it because it reflected my intentions impeccably.

BB: With the proliferation of fast-fashion, and the endless cycle of trends, is there still a place for narrative and meaning behind garments?

When I design it has to have meaning, as designers we are required to react to the world around us and question it. For me it so important to take inspiration from an endless variety of sources and materials around us and having a voice in today’s world needs to be utilised within fashion. This is further put into question with the climate crisis, as young designers, we need to question our current system of how and why we produce clothes.

This is easier to do is an individual, I don’t believe larger corporates bring that narrative to their brands. Especially on the high street, people want basics and at low costs, you aren’t going to get deep meaning from a tank top from a fast-fashion retailer. The concept of sustainable fashion and greenwashing media coverage needs to utilise. Sustainable fashion should be fashion not a separate section for the more privileged in society to shop.

BB: What does Britishness mean to you in the 21st Century?

SM: Tough question asking an Irish woman this. Britishness for me has evolved over the past four years from living in Belfast, London, and Amsterdam. To identify as British brings with it a lot of stigma surrounding Brexit. How did you vote and why are the main questions asked? Britishness in itself has developed into several different strands for me. The idea of British Nationalism being one, this concept for some that Britain is better of alone, in some spheres and a fuller more inclusive Britishness that involves a more globalised view of nationalities under the term British. The divide I have found is predominately age-related with British youth being very politically and socially aware and celebrating the EU for what it has done for them and acknowledging identity in a more inclusive manner.

BB: We know of the vast impact Brexit is forecasted to have on the fashion industry, but Sophia, have you felt the ramifications of Brexit in your own personal lived experiences?

Yes. It’s always a very topical point of conversation coming out of art school you realise how much of a bubble you live in. I have had the opportunity to live and work with people all over Europe and the world. Some of my best friends are from overseas.

The biggest issue I have found is the mentality of people speaking about this. It opens up such bigotry and xenophobia. To have the opportunity to do Erasmus I met some incredible creatives, friends, and colleagues. Closing off this opportunity to the youth of today is hindering our development and growth, why would a government do that? To allow people to travel freely and experience new cultures is far more educational than any textbook.

In relation to myself, it leaves the youth of Northern Ireland to question being an Irish citizen. I was born with dual nationality and can have both a British and Irish passport. This is due to the Good Friday Agreement allowing citizens of Northern Ireland to identify as either nationality. However, with the ramifications of Brexit, this is in jeopardy and puts the rights of being an Irish citizen in jeopardy.

BB: What does Home mean to you?

SM: Where the craic is.

BB: Are there any current issues/themes you plan on exploring in future collections?

SM: There is so much more I want to delve into within my past, I feel I’ve only just started and want to explore further. I want to develop my pattern cutting skills and tailoring to challenge traditional menswear silhouettes for the modern man.

In terms of subject matter looking at men who are on the anarchists of society and the artwork and graffiti. My next project is a fake political campaign drawing on my graduate collection to call on everyone to think of the European Youth before they go to the polls to vote, keep an eye out for that around London.