IN CONVERSATION: JAMES MASSIAH

Art/Culture

IN CONVERSATION: JAMES MASSIAH

James Massiah is a man of many forms. Having grown up a devout evangelist before leaving the church in his later teens, his way with words has taken him overseas, across ad campaigns, festival stages and commissioned by the monarchy. Branding his work as ‘Party Poetry’, he’s equally comfortable holding an intimate free for all at The Haggerston as he is delivering a piece to the city’s elite at Fashion Week, or hosting proceedings at Boiler Room. Regardless of which side of James you’re getting, you can be sure it’s him through and through, with all the funk in between. We spoke to the London polymath about his background, Amoral Egoism, and the power of language in 21st century Britain before he performed at ‘Coded Language.’ An evening of discussions on the heritage and development of Multicultural London English at the British Library as part of Red Bull’s inaugural London Music Festival.

Words:

Louis Olivier

Imagery:

Connor Carver-Carter

Multicultural London English is a product of lived experiences. As a poet who hails from south London yourself, would you say your use of language been influenced by London?

Definitely. Growing up, I remember mimicking accents of older people at church, shopkeepers, bus drivers, everyone I met. Eventually, you get to an age where you hear the older guys say “oh that’s wicked, that’s heavy”, and you’ll pick it up. You don’t know what it means, or where it comes from, but it fits the environment. You gain a sense of belonging through language and through those moments.

You were heavily involved in the church until your teens. What impact has religion had on your appreciation for words?

In a lot of interviews, I speak about my early influences – Roald Dahl, the King James Bible (which my church followed), but then also Wiley, Dizzee Rascal and Roll Deep. The older guys in my church would give me tapes of theirs, and I would go home and write the lyrics down and try and dissect what it meant. Like what does chung mean? I would be absorbing stuff. As far as religion itself goes, there was a period where I was really into Islam. There are Arabic words I say now that are still part of my slang. Like “Ah yeah, inshallah, see you tomorrow bro”. Anything I say now that isn’t just straight-up English is said in a tongue in cheek way. I think that’s testament again to the city I grew up in more than anything.

Code-switching is prominent within your work. How do you know when to switch, and why do you use that as a tool?

My dad was born in Barbados, and he came to the UK when he was 11. He’ll be on the phone to someone in Barbados, and he’ll change his voice to convey something to the person he’s communicating with. In the same way, if I’m speaking to an old lady on the bus – independent of what background she’s from, I probably won’t be like, “Yo wagwan, is it cool if me and my bredrins sit there?”. I want her to understand what I’m saying in the most direct way possible.

I think switching between code is prominent with my work as it’s part of my personal philosophy. It’s to do with the value related to art, a question of high culture and low culture – the idea that someone who looks like this or is from this background shouldn’t be able to speak like this, and someone from a higher-up place would never stoop to those depths. I like to twist that ideal and straddle both sides of it.

It’s also a dog whistle. The people who relate to my work, at least from the people I meet, are very specific kinds of people – who exist on the junction on a lot of different worlds and have a deep knowledge and understanding of the worlds they are involved in. They’re not just passengers – they’re attentive. They can find value in my work because it’s an experience they’ve had, or something I’ve been interested in that I articulated.

Tupac’s whole thing was a character. He was like, “I’m a black man in America”. He knew people perceived him as gangsta, despite how intelligent he was, but the way he saw it was; if someone breaks into your house, you’re not going to be like, “Hey, excuse me”. You’re going to be like “What the fuck is up?”. That’s what I’m doing. That’s Multicultural English to me.

“

I HAD TO FIND THE POETRY THAT CUTS DOWN THE MIDDLE – WHETHER YOU’RE RIGHT-WING, LEFT-WING, PRO-LIFE, PRO-CHOICE WHATEVER. A POEM THAT COMES IN AND SLAPS YOU IN THE FACE.

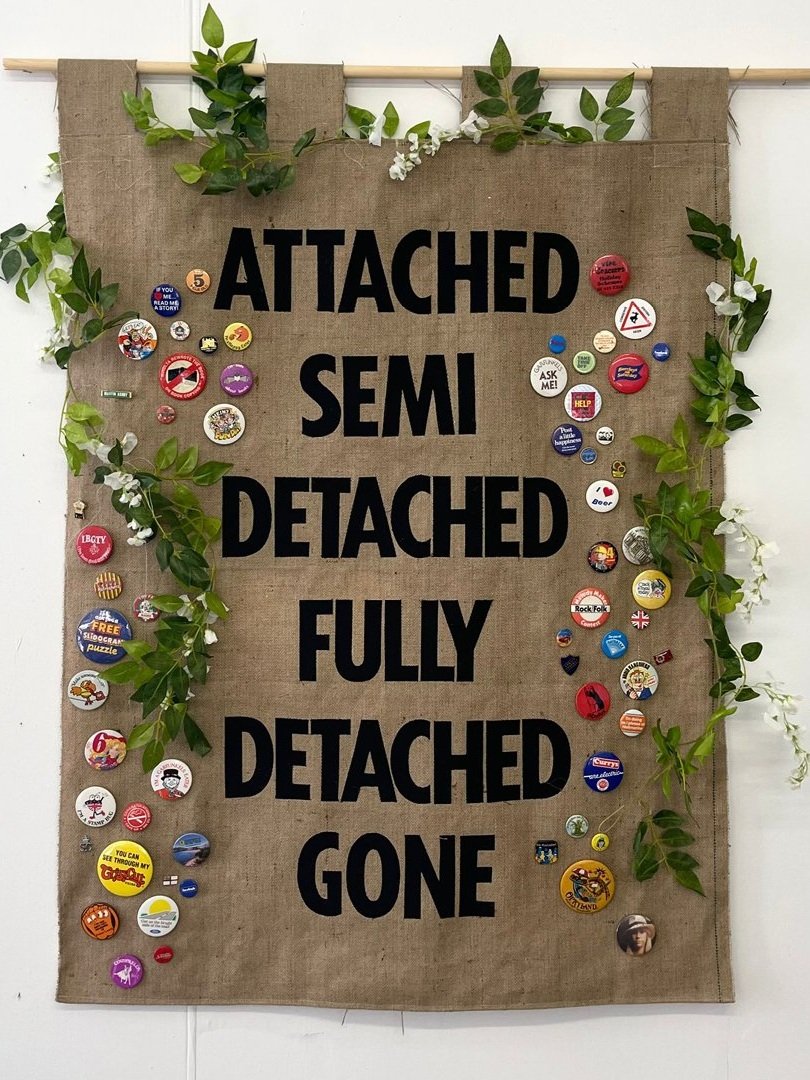

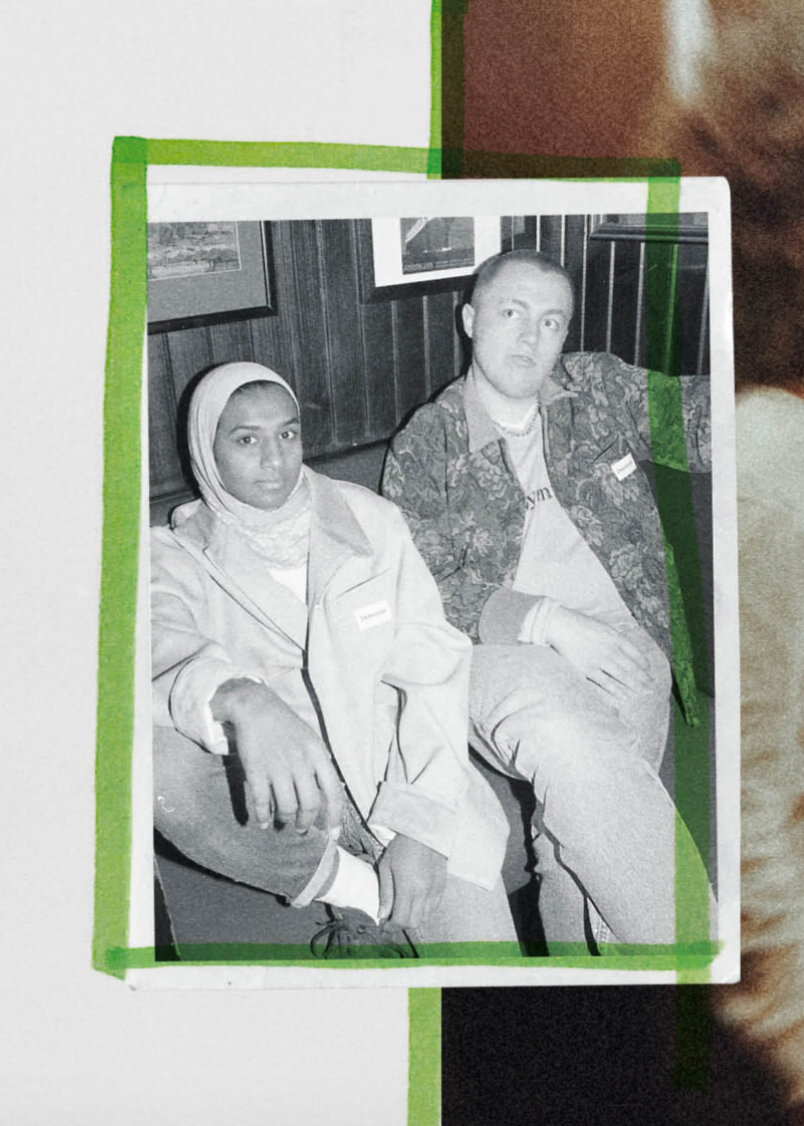

CAPTION GOES HERE: LORUM IPSUM

CAPTION GOES HERE: LORUM IPSUM

Your poems cover a breadth of topics from knife crime, sexuality, religion and the monarchy, where do you draw linguistic inspiration from? And why do you think these themes are so prevalent in your work?

PIMP by Iceberg Slim had a big effect on me. I look at Funk as one of history’s most important cultural movements because of what it spawned – hip hop, house, and the attitudes of those genres. It’s that jive talk – even within dancehall, and Jamaican yardie culture, there’s a similar thing. It’s vulgar, it’s crude, it’s disgust. The language needs to be that. That’s what our experience is. Like how the musicians behind that movement were in the slums, shooting junk, the message had to be authentic.

I think it was Allen Ginsberg who spoke about ‘speaking the American Language’. That really resonated with me – I don’t see any point in reverting to some old English way of speaking. We’re around in this day and age and I’m going to speak as I do every day.

Your work is often seen through screens – video, music, a degree removed from the audience. Does your experience of reciting poetry change when it’s to a live audience rather than to a camera?

The words change – sometimes I look out into the audience, and I’ll be like, I’m not going to say that word. Other times I look out and I’ll be on home turf – at the Haggerston at my own event, and I’m like I’m gonna say it. I do sometimes change the words, based on who I’m speaking to.

Your more recent work has included more minimalism and speaking with quite direct language. Some poets will dance around a subject, while you choose short lines to deliver your message. Is that a conscious choice?

Yeah, 100%. I used to write long poems because I wanted to prove that I could do it. There’s a Gil Scott Heron quote that says, “audiences don’t understand poetry, and their response is – hey, this must be deep!” That was me for a while. But there was something missing – people would tell me they love my work, but none of them would know my poems. I doubt any of them would say them on their own. I decided that I had to make that happen.

I wanted something straight and memorable, so I thought I’d start writing hooks in the form of poetry. Initially, it was funk poetry, but now I call it Party Poetry. I love the idea of being in a party, and someone’s like “read a poem, read a poem”. That’s what I’m trying to create.

How do you think that affects the reception of your work?

The worlds that I move in now, I never thought I’d see or get access to. There’s a core in most people that I meet, where they’re searching for something. If you’re searching, doesn’t matter what your colour or sexuality is, then you will appreciate my work. I may have given up on the dream of being a huge star. It’s still there, I ain’t gonna front, but I have a certain degree of comfort in knowing that the people who are aware of it and are sharing and talking about it, are the kind of people I’d think of as intellectual equals or my superiors.

You’ve even played with language in a philosophical sense – namely through the A and the E. Could you briefly explain Amoral Egoism and where that came from?

The A – Amorality, and moral nihilism. The idea that nothing is objectively right or wrong in a moral sense. Egoism is the idea that an individual will always do what is right for them. In a nutshell, right and wrong are determined by an individual, when it comes to questions of morals or ethics. If a tree falls in a forest, does it make a sound? You can argue about that over there. Was it wrong that you cut down that tree? Was it wrong that I didn’t pick up the tree? or that I didn’t save the environment? Who knows, you tell me. It’s up to each individual.

“

THERE’S A CORE IN MOST PEOPLE THAT I MEET, WHERE THEY’RE SEARCHING FOR SOMETHING. IF YOU’RE SEARCHING, DOESN’T MATTER WHAT YOUR COLOUR OR SEXUALITY IS, THEN YOU WILL APPRECIATE MY WORK.

Why did you bring this into your work?

Because of language. Words like guilt, shame, good, bad. The whole idea of a ‘good’ poem had been changed with the woke explosion. Something would be classed as a bad poem because they used a slur, or they didn’t centre someone of a certain background. Having left the church, I still had a sense of right and wrong. But once this stuff started happening, I didn’t know what was good or bad anymore. Things that people used to do weren’t cool anymore. Wokeness basically made me go to Wikipedia and figure it out.

I didn’t read for a long time, almost out of Kanye West-esque arrogance. But once I delved into the classics – Brave New World, Bell Jar, The Outsider, Picture of Dorian Gray, Clockwork Orange, Anthem by Ayn Rand my perspective completely changed. To me, they’re all morality tales, asking what I should be doing as a person. I wanted to find a way to express that. No one was engaging with this material, and therefore weren’t willing to have conversations about the meat of these books.

The A and the E idea originally started as this idea of us being all equal – and the idea that poetry can unite everyone together. But I realised that all the people who were into this message voted left and were into Labour or Green. I wanted to know where the people who disagreed with these ideas were. The idea evolved into allies and enemies coming together to have these discussions, but still, this wasn’t happening. As a result, I had to find the poetry that cuts down the middle – whether you’re right-wing, left-wing, pro-life, pro-choice whatever. A poem that comes in and slaps you in the face.

What does home mean to you?

Playboi Carti – Home.

What do you hope to achieve through your poetry?

The lofty ambition is to have Amoral Egoism on the school curriculum. Or Party Poetry. I’ll do either. I guess Amoral Egoism on the Philosophy BA, and Party Poetry on the GCSE English reading list.

You just released Natural Born Killers, and we know there’s an EP on the way. How has that transition been into music, and what place do you think poetry holds in music?

For a long time, I was scared to come out as a musician, because of the perception of how black male artists are viewed and the boxes you get put into. A lot of my influences in the music were Chicago house stuff, grime stuff, dub poetry, Linton Kwesi Johnson, John Cooper Clarke, the Clash.

For this track, there’s a song by Talking Heads called Seen and Not Seen, which was the main inspiration. It’s this driving repetitive beat, and David Burns talking over it. I wrote this as a way of delving into that funk influence – to get into the audience’s fucking heads. Give them something to walk away with.

My dad heard it yesterday, he told me it was terrible. He cut me down to size. But for me, It’s my proudest work because it’s achieved what I wanted it to achieve. Something that sticks in someone’s head, with a hook that hypnotizes you.